By Angel Niño Torres and ACSS researchers

July 30, 2022

Cryptocurrency has presented several challenges for regulatory entities since Bitcoin’s introduction in 2008. Buyers and sellers online were quick to enjoy cryptocurrency’s relative anonymity and expedience, which also led to criminal activity.

Nearly a decade and a half later, cryptocurrency is an expansive and dynamic financial system with almost a $1 trillion market capitalization. Like fiat currency, crypto is used for legitimate purposes, such as payments, investment ventures, banking and fundraising.

Congruently, crypto funds criminal ventures, such as financing terrorism and illicit trafficking, and money laundering. Anonymity and speed greatly facilitate parties wishing to obscure their dealings.

Such parties can include terrorist organizations, criminal elements and sanctioned countries. The ability of regulatory bodies to apply sanctions programs to cryptocurrency helps ensure the efficacy of sanctions programs.

What Can Be Sanctioned?

Applying sanctions to activities involving cryptocurrency can take shape in multiple forms.

- They can fall under a state’s existing financial enforcement mechanisms.

- Cryptocurrency addresses, virtual asset service providers (VASPs) and other crypto-service entities can be the targets for enforcement.

- Whole digital currencies can be sanctioned.

The following case studies highlight the specific threats that cryptocurrency sanctions try to counter.

Digital Currencies and CBDCs

One of the first state-backed cryptocurrencies has been Venezuela’s petro. Within a month of its launch in February 2018, the petro prompted one of the first executive orders on crypto and sanctions: EO 13827. It states that any “digital currency, digital coin, or digital token that was issued by, for, or on behalf of the Government of Venezuela on or after January 9, 2018, are [sic] prohibited as of the effective date of this order.”

Before issuing EO 13827 and the launch itself, the US Treasury perseved Venezuela’s initial coin offering for petro cryptocurrency as a regulatory risk, citing it could violate US sanctions against Venezuela. This was based on the sentiment that transacting with Venezuela’s digital currency may portray an extension of credit to the Venezuelan government.

In March 2018, an executive order from then President Donald Trump prohibited transactions in any Venezuelan government-issued cryptocurrency by a US person or within the US. This came after a claim that the petro was designed to purposefully bypass US sanctions and access international financial systems.

With the rise of countries’ use of blockchain technology, a relationship between sanctioned states and cryptocurrencies may be seen more often. One particular case is that of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), which have the potential to be a regulatory challenge.

International CBDC networks are proliferating in Asia, such as the mCBDC Bridge, involving Thailand, Hong Kong, China and the United Arab Emirates. Russia’s central bank is working on a digital rouble. Former US Treasury official Michael Greenwald told CNBC: “What alarms me is if Russia, China, and Iran each creates central bank digital currencies to operate outside of the dollar and other countries followed them”.

North Korea’s Use of ‘Mixers’

North Korea falls under the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) DPRK sanctions program. This omnibus approach provides a basis for the US to designate entities and activities for intersecting with North Korean efforts related to criminal activity, finance, or threats to international security.

Lazarus Group is a DPRK state-sponsored cyber-hacking group. Lazarus Group has been responsible for some of the largest cyber-heists, such as the Bangladesh Bank heist in which the group stole $101 million purely by hacking.

The largest virtual currency heist ever was committed by Lazarus Group. This year, $620 million was defrauded by Lazarus Group from the blockchain managing the online game Axie Infinity. Of that $620 million, $20.5 million was laundered with a website known as Blender.io. Blender.io provides the services of a mixer. Mixers obfuscate ownership and are a common method of laundering crypto. Simply, crypto is deposited into a pool of funds, and the deposit is returned to the owner without a traceable trail.

OFAC determined the usage of Blender.io by Lazarus Group and then applied sanctions to Blender.io as part of its cyber-sanctions program. Lazarus Group had been sanctioned since 2019 under the DPRK program. The OFAC Sanctions List Search application shows the cryptocurrency addresses, as well as websites and emails designated as part of Blender.io, are listed.

Separate cryptocurrency addresses attributed to Lazarus group also are listed by the application. Blender.io is the first mixer to be sanctioned by the US Treasury.

Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Brian Nelson stated that “[virtual] currency mixers that assist illicit transactions pose a threat to US national security interests. [The Treasury is] taking action against illicit financial activity by the DPRK and will not allow state-sponsored thievery and its money-laundering enablers to go unanswered.”

Since this action, all property and interests in Blender.io that is in the US or in the possession or control of US persons are blocked and must be reported to OFAC. Entities owned 50 percent or more by Blender.io are also blocked.

As for the perception of mixer services by the regulatory community, it can be said that, due to their function of purposely obfuscating asset ownership, they imply risk. The case of Lazarus Group and Blender.io displays a nation state’s ability to utilize the cryptocurrency environment to enact malign operations.

Crypto VASPs as Laundries

Ransomware is a dynamic and relatively new threat that has troubled individuals, businesses, and state institutions for several years. Targets such as the UK’s National Health Service and the US’s Colonial Pipeline system, among others, have shown that integral services and infrastructure mechanisms can be nearly halted at the whim of ransomware perpetrators.

Ransomware schemes are diverse and are deployed on many scales and with differing methods. Put simply, ransomware infects a computer system with an encryption mechanism preventing access to files without a method for decryption.

To regain access, victims are prompted to send money to the attackers, like paying a ransom. The preferred method of ransome payments is cryptocurrency.

Ransomware operations, and the high crypto-enabled payouts that they accrue, have caused regulators to develop sanctions strategies to curb their efficacy. OFAC’s goal is to counter ransomware as part of a whole-of-government effort.

To this end, a significant step made by OFAC was the sanctioning of Chatex. Chatex is a VASP based in Latvia. Chatex and its network of affiliate services facilitated financial transactions for ransomware actors. When undergoing blockchain analysis, Chatex’s transactions show that “over half are directly traced to illicit or high-risk activities such as darknet markets, high-risk exchanges, and ransomware.”

A related party in this scheme is Suex. Suex is another crypto-financial service and functioned as another exchange to conduct transactions in this pipeline of ransomware funds into the crypto ecosystem.

Simply, Chatex and Suex were handling the funds obtained from ransomware schemes. Service providers such as these are expected to conduct due diligence and enact know-your-customer protocols. By allowing their services to facilitate transactions with known criminal elements, the grounds for OFAC’s designation are clear.

IZIBITS OU, Chatextech SIA, and Hightrade Finance Ltd are affiliates in a support network for Chatex’s infrastructure and were also sanctioned. The precedent of the sanctioning of Chatex and Suex displays OFAC’s ability to identify actors in the crypto space enabling crime and removing their ability to engage with legitimate parties.

Ransomware Operators

Individuals on OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals And Blocked Persons List (SDN) find that their fiat currency activity is subject to obstacles. Their cryptocurrency activities are intended to be no different.

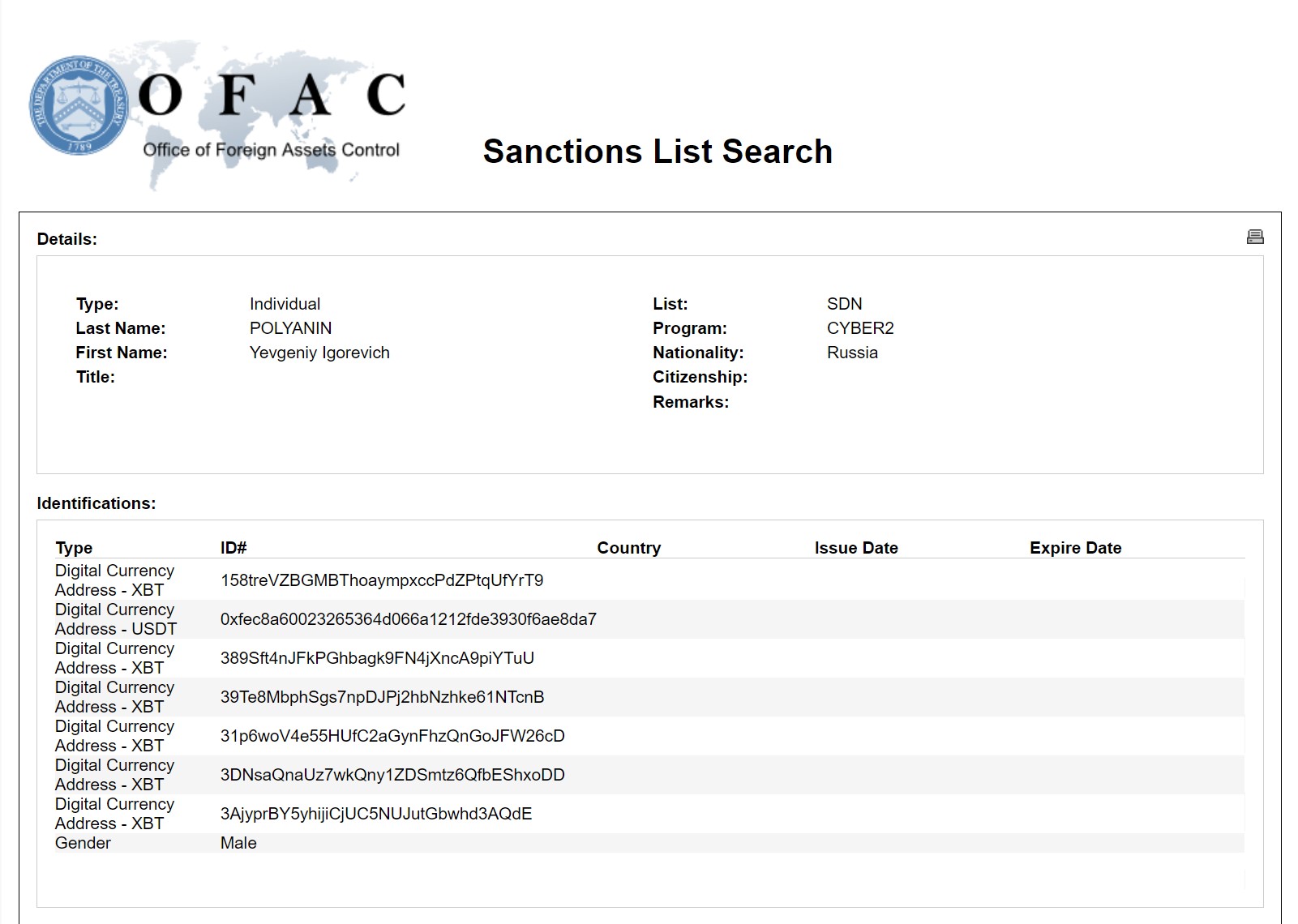

Addresses and wallets designated to belong to an individual are paired with other information that comes back on an SDN search, such as Yaroslav Vasinskyi and Yevgeniy Polyanin. These Ukrainian and Russian nationals, respectively, were responsible for participating in ransomware operations against private businesses and persons in the US. Both operated as part of the Russia-based Ransomware-As-A-Service (RAAS) entity REvil, also known as Sodinokibi.

Over their ransomware careers, both collected $200 million in ransom payments paid in Bitcoin and the privacy coin Monero. Vasinskyi and Polyanin were arrested by their home states in 2021. Their bitcoin addresses are sanctioned by OFAC and can be found through a search of the SDN list.

The addresses are illegal to interact with. Known activity, if any, should be reported to OFAC. Property, including the cryptocurrency of the designated targets subject to US jurisdiction, is blocked, and US persons are generally prohibited from engaging in transactions with them.

The sanctioning of cryptocurrency addresses designated to belong to sanctioned individuals ensures a thorough approach to crypto, which in this case is treated with the high scrutiny that accompanies fiat currency.

SDN search results for Yevgeniy Polyanin with cryptocurrency addresses attributed to them. Note that the digital currency address connotation is “XBT”, which means Bitcoin. Source: https://sanctionssearch.ofac.treas.gov/Details.aspx?id=33858

Considerations for Compliance

Although there are public sector entities, projects and cryptocurrencies subject to sanctions, the cryptocurrency environment mainly comprises the private sector. In October 2021, OFAC published the Sanctions Compliance Guidance for the Virtual Currency Industry to summarize its approach to designation and enforcement of virtual assets, and to refer parties to official resources.

Awareness of the threats at the nexus of cryptocurrency and financial crime is imperative. State-sponsored hacks, state-managed digital assets, ransomware and cutting-edge obfuscation techniques are only a few areas exploited with crypto. Sanctioning cryptocurrency and related mechanisms is often necessary to ensure effective regulation and enforcement.

Angel Niño Torres is a member of the ACSS Editorial Task Force (EdTf). Certified AML FinTech Compliance Associate (CAFCA). Head of compliance for Coinbag (Ireland). Sanctions researcher for PST.AG (Germany). Professor of business law at Universidad Rafael Urdaneta (Venezuela) in the Schools of Law and Business Administration. CEO of FTT Lawyers (Venezuela)