August 07, 2020

By: Jack Walsh, Reporter ACSS

For compliance officers, particularly those working for non-U.S. companies, the proliferation of secondary sanctions in recent years has introduced an array of challenges.

By imposing secondary sanctions, the U.S. extends its influence over foreign parties (who may have no business contacts with the U.S.) for simply having engaged in an activity that is contrary to U.S. policy goals.

A recent example is the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for 2020, a new piece of U.S. legislation that imposed sanctions aimed at vessels and foreign persons that are participating in the construction of the nearly-finished Russian natural gas pipelines to Europe, including Nord Stream 2.

The NDAA provides for the imposition of U.S. sanctions against:

- vessels engaged in pipe-laying at depths of 100 feet or more below sea level for the construction of the Nord Stream 2 and Turk Stream pipeline projects and any successor projects; and

- any foreign persons that have knowingly “sold, leased, or provided” such vessels for the pipelines or facilitated deceptive or structured transactions to provide such vessels.

The law provides that every 90 days, the Secretary of State, in consultation with the Treasury of Treasury, shall identify these vessels and persons. The sanctions to be imposed include blocking sanctions and a travel ban.

Almost overnight, the threat of secondary sanctions precipitated the exit of Allseas, the Swiss company contracted to lay the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, halting construction in its tracks.

Primary Sanctions vs. Secondary Sanctions

Both primary and secondary sanctions are largely implemented and enforced by the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC).

U.S. primary sanctions contains prohibitions in which U.S. persons and entities may not engage. They also prohibit transactions with a direct nexus to the U.S. In the context of sanctions law, a U.S. nexus denotes commercial involvement with a U.S. person or U.S. origin product, software or technology, and includes collateral commercial activity within U.S. territory.

While primary sanctions contain prohibitions for U.S. person, it is important to note that non-U.S. persons can also engage in U.S nexus transactions and thereby violate U.S. primary sanctions. Foreign companies with sufficient levels of contacts with the United States, and which commit sanctions violations, face potential OFAC civil enforcement actions and criminal prosecution by the U.S. Justice Department.

Secondary sanctions, on the other hand, target foreign individuals and entities for engaging in specified activities that may not necessarily have a U.S. nexus. They place pressure on non-U.S. third parties to cease commercial relations with a sanctioned entity by restricting the third party’s access to the U.S. market and financial system.

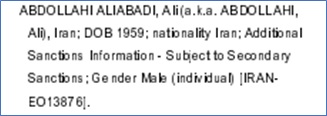

When OFAC adds the words “Subject to Secondary Sanctions” to the name of a designated entity or person on the SDN list, any foreign entity that continues to conduct business with that sanctioned party may find itself denied export licenses, loans, export-import bank assistance, and, in extreme cases, total loss of access to the U.S. financial system, including U.S. dollar-denominated transactions.

If the foreign entity doesn’t comply, it may be placed on the SDN list itself.

Due to the sheer stature of the U.S. market and the global, outsized role of the U.S. dollar, these penalties represent a crippling, hazard for multinational firms. The U.S.’ tremendous economic leverage is what allows secondary sanctions to have an extraterritorial reach and makes this policy weapon so potent.

Note that being targeted with secondary sanctions is not a civil or criminal enforcement proceeding, nor the imposition of a penalty thereunder. It is, in fact, an extrajudicial process for violation of a U.S. policy.

Case Study: Chinese buyer of Iranian Oil

In July 2019, a Chinese company, Zhuhai Zhenrong Company Limited, and its CEO were both targeted with secondary sanctions for knowingly purchasing or acquiring oil from Iran.

The sanctionable behavior consisted of engaging in a “significant transaction” involving Iranian crude oil after the expiration of China’s Significant Reduction Exception.

The sanctions were imposed under E.O. 13846 of 2018. Section 3 (ii) of this Executive Order authorizes the imposition of sanctions for persons determined to have: “on or after November 5, 2018, knowingly engaged in a significant transaction for the purchase, acquisition, sale, transport, or marketing of petroleum or petroleum products from Iran.”

Recent Developments

Following the United States’ withdrawal from the JCPOA and the reinstatement of severe primary sanctions on Iran in 2017, the threat of secondary sanctions effectively forced global financial institutions to choose between halting transactions with Iranian banks and losing access to the U.S. financial system. More recently, in May, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced the termination of sanctions waivers covering all remaining JCPOA-originating nuclear projects in Iran. While the long-term effect of this development will ultimately hinge on how aggressively OFAC and Department of State choose to pursue action against non-U.S. parties that provide assistance to the Iranian government, it nonetheless expands the scope of sanctionable targets.

Elsewhere, OFAC has leveraged existing programs targeting the Maduro regime to sanction non-U.S., non-Venezuelan parties that facilitate Venezuela’s oil trade, as well as other sectors of the country’s economy. Designations include affiliates of Russian oil firms and Greece- and Marshall Islands-based maritime shipping companies. Most recently, the U.S. government levied sanctions against three Mexican nationals for purportedly operating an “oil-for-food” program that never resulted in food deliveries to Venezuela. This was one of OFAC’s more aggressive and provocative actions to date, and sends yet another stern warning to non-U.S. actors involved with Venezuela-related dealings.

Compliance Implications and Challenges

Non-U.S. firms

For many non-U.S. firms operating in overseas markets, the opacity of secondary sanctions laws poses a significant compliance issue. Local compliance officers do not have, and cannot realistically be expected to have, sufficient expertise in this specialized area of U.S. law, particularly when business operations do not have a U.S. nexus. Moreover, OFAC has issued minimal guidance on the scope and impact of secondary sanctions and has conducted limited outreach to non-U.S. parties. Non-U.S. companies that desire to refocus their risk management approaches to account for potential OFAC scrutiny simply are not provided with a clear course of action.

A lack of clarity on how to interpret secondary sanctions has led to a high degree of over compliance among large European companies. Many have opted to completely sever commercial ties with Iran rather than risk inadvertently running afoul of U.S. secondary sanctions. Siemens and Airbus, among other corporations, each cancelled multi-billion dollar contracts with Iranian state companies following the reinstatement of U.S. secondary sanctions in 2017.

Inconsistent Enforcement

Another challenge for non-U.S. compliance professionals has been the inconsistent enforcement of secondary sanctions. OFAC and other U.S. government offices exercise considerable discretion when designating foreign individuals, businesses, and other third parties, often pursuant to broader, and not necessarily connected, foreign policy objectives.

In 2018, for example, the Trump administration imposed secondary sanctions on a Chinese company for engaging in significant transactions with Russia’s principal arms export entity, Rosoboronexport. The Chinese firm, Equipment Development Department, was determined to be in violation of the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), which mandates sanctions on any entity that “engages in a significant transaction with a person that is part of, or operates for or on behalf of, the defense or intelligence sectors of the Government of the Russian Federation”. Yet less than a year later, the U.S. government elected not to impose sanctions on Turkey, a NATO ally, after the Turkish military acquired the same S-400 missile defense system from Rosoboronexport.

The inconsistent application and enforcement of secondary sanctions makes it quite difficult for non-U.S. compliance officers to conduct thorough and accurate risk assessments. As the U.S. government’s disparate responses to Chinese and Turkish dealings with Rosoboronexport indicate, the enforcement of secondary sanctions is not a cut-and-dry legal matter, but rather proves to be very much a grey area.

U.S. Entities

While U.S. persons need to comply with all U.S. sanctions laws, and non-U.S. persons mainly have to focus on U.S. secondary sanctions laws, there is a further, indirect way in which U.S. compliance professionals need to think about secondary sanctions. Increasingly, it is expected that U.S. businesses will conduct due diligence on whether their non-U.S. counterparties comply with U.S. secondary sanctions. Even though this is not an explicit OFAC requirement, recent advisories from OFAC, particularly in respect to the maritime shipping sector, make clear that “knowing your customer’s customer” may be an expectation, at least in certain riskier contexts.

The E.U. Strikes Back

European businesses now face mounting pressure from the European Commission, as well as from their national governments, to push back against the reimposition of pre-JCPOA secondary sanctions – something the E.U. perceives as an excessive and unreasonable assertion of U.S. sovereignty.

In 2018, the EU announced new amendments to the Blocking Statute, Regulation 2271/96, which aims to shield E.U. businesses from “the effects of U.S. sanctions on E.U. economic operators engaging in lawful activity with third countries”. Long-regarded as a rather toothless piece of legislation, the amended statute signals the E.U.’s dedication to the full and effective implementation of the JCPOA, and introduces new penalties for any E.U. company that ceases business with/in Iran as a hedge against potential secondary sanctions.